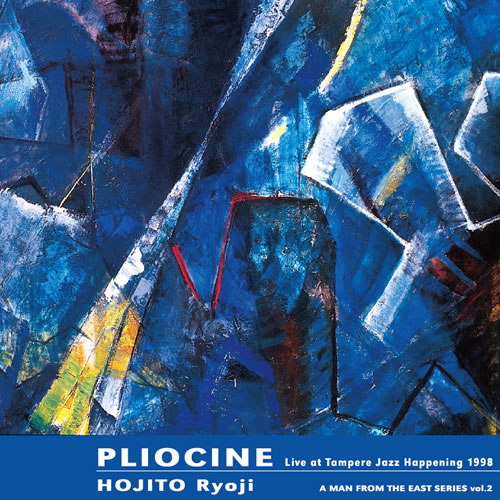

darko: dkcd02

Pliocine: Live at Tampere Jazz Happening 1998

A MAN FROM THE EAST SERIES, VOL. 2

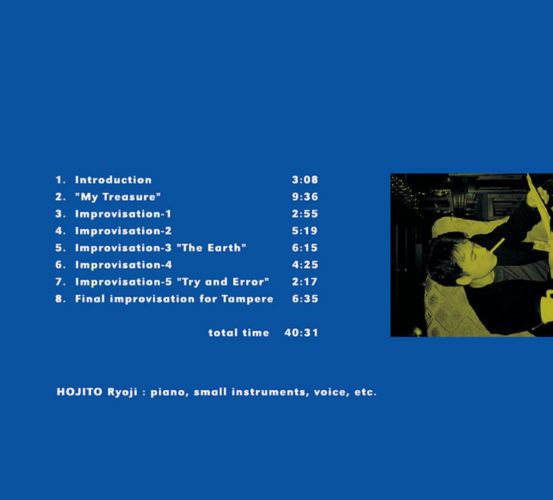

01 Introduction (3:08)

02 My Treasure (9:36)

03 Improvisation-1 (2:55)

04 Improvisation-2 (5:19)

05 Improvisation-3: The Earth (6:15)

06 Improvisation-4 (4:25)

07 Improvisation-5: Try and Error (2:17)

08 Final Improvisation for Tampere (6:35)

All music composed and performed by Ryoji Hojito

Ryoji Hojito: piano, small instruments, voice, etc.

Recorded live by Tapio Ylitalo at the Tampere Jazz Happening, Finland on November 1, 1998

Sound improvements and mastering by Yoshihiro Tsukahara in Sapporo, January-March 2000

Cover painting: Miyo Hojito

Photography: Yoshiko Hojito and Takashi Homma

Design: Takashi Homma

Includes liner notes by Daisuke Fukuchi in Japanese and English (English translation: Cathy Fishman and Yoshiyuki Suzuki)

Released July, 2000

レーベル:darko(ダーコ)規格番号:dkcd02

Released July, 2000

CD通販:Callithump

Daisuke Fukuchi

(assistant curator of Kushiro Art Museum, Hokkaido)

Hojito Ryoji is a musician who practices a form of musical expression that makes use of the entire piano, thereby expanding the expressive range of the piano as an instrument. His playing style looks highly eccentric. To obtain a unique sound, he puts various and sundry objects inside the piano–a wooden block, a piece of foam styrene, a bowl of coffee beans, an electric toothbrush, and so on–having predicted their effect on the sound. These objects unite with the strings and frame of the instrument; and then the strange resonance they produce turns into novel and unforgettable harmonic overtones which are conveyed into listeners’ ears.

The piano is an instrument which normally is played by hitting the keys on the keyboard. Although it is a very large instrument, players generally use a very limited part of it for musical expression–the keyboard and pedals. But it seems only natural to conceive of extending the instrument’s expressive power by manipulating the strings or hammers, which are the actual sound generators. It seems natural, I should say, provided one does not regard the inside of the golden frame, surrounded by the jet black board with its mirror-like reflection, as the forbidden world of a Buddhist family altar.

In fact, in countries where people have never seen or heard of Buddhist altars, there was nothing new about handling the internal structure of the piano. John Cage composed a work for prepared piano 60 years ago. Going further back, Henry Cowell in the 1920s innovated the technique of plucking and tapping the piano strings. Cage’s work for prepared piano came into being when he had to use the piano in place of percussion instruments in composing music to accompany performing arts. First he considered various sounds coming out of the prepared piano as substitutions for the tones of percussion instruments; and then he attempted to produce rhythms which would enhance the richness of these tones.

Cage brought an element of uncertainty to music. In the world of music, any form of expresson is OK as long as it is based on a clear theory; and originators are respected. Guided by this way of thinking, which at first glance seems rather rough, Cage broke new ground, making a remarkable contribution to the liberation of music from an area closed in by musical grammar. Ironically, however, the practitioners of academic contemporary music did not take advantage of this newly obtained freedom to move toward the creation of a new world where the range of human sensitivity would be expanded. Rather, it attached greater importance to the verification of the environment in which music comes into existence, and tended toward analytical expression and the exclusion of the composer’s and musician’s consciousness and subjectivity from the composing and playing processes. Thus, the prepared piano was buried along with most of 20th-century experimental music, lost its life force as a tool of musical expression, and remained in people’s consciousness only as a term recalled from musical history.

Such were the prevailing musical conditions when Hojito Ryoji–coming from a completely different background–began his musical activity with a mode of expression making use of the entire piano. He attempts to eliminate traditional tonality and rhythm from his melodies and tone, but at the same time there is a very lyrical side to his playing. This is undoubtedly because he did not create his style via a methodology of pure experimentation with technique and tone; rather, he arrived at his style via the profound emotion which he wants to express, and the motifs which he wants to develop.

For example, in pieces that begin on just the keyboard, there are motifs which convey feelings such as tenderness and nostalgia. In particular, the expression in the first motif of the second tune “My Treasure,” with its pentatonic progression, seems very natural for a contemporary Japanese person. This is not an orderly form of expression based on an individual concrete memory or everyday feeling; it is a form of expression that comes from the primordial chaos which exists inherently in the human heart. The substance of Hojito’s improvised expression lies in the music which a player reproduces through the filter of sensitivity, by subconsciously capturing outlines of images from the deepest part of the universal human consciousness.

In the fifth tune on this CD, Hojito makes a fat sound (playing a cylindrical instrument(?) with a saxophone mouthpiece). The call of a humpback whale provided him with the inspiration for this sound. The low-pitched, melancholy phrases effectively express the grief that lies deep within the hearts of whales and other living creatures whose habitats have been destroyed. This kind of expression could never be the product of superficial cleverness or a haphazard idea.

Listening to Hojito’s performance you will undoubtedly experience many delicate moments that sparkle like jewels, provided you pay attention not to the the unconventional playing style or the power of the performance, but to what can be expressed only in this style, and to the feeling it produces. If you do, you will surely discover the process in which each sparkle–that is, each motif–develops with richness and breadth.

The performance on this CD was recorded at the Tampere Jazz Happening ’98 in Finland in October of that year. Hojito played on the final day of the festival. Not only was his performance very well received by the audience, it also made a strong impact on the staff and other musicians who participated in the festival. His music caused such a sensation that the following day the Finnish newspapers gave him extensive coverage; and apparently, many of the people who were taken with his performance at Tampere hurried to go and see the concert held a little later at KIASMA (Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, Finland).

The Finns have always appreciated the kind of clear-toned, expansive expression exemplified in the works of Sibelius and Palmgren. Hojito’s performance in that time and place must have touched the hearts of the Finnish people in a different way than it touches the hearts of Japanese.

福地大輔(北海道立釧路芸術館学芸員)

――宝示戸亮二はピアノ全体を使った音楽表現を繰り広げ、楽器としてのピアノの表現領域を拡大する活動を続けている音楽家である。彼の演奏スタイルは、見かけ上は非常にエキセントリックなものである。彼は独得な響きを求め、その効果を計算した上で多種多様なものをピアノの中に持ちこむ。木片、発泡スチロール、ボウルに入れたコーヒー豆、電動歯ブラシ……。ピアノの弦やフレームと一体化した物質から響く不思議な共鳴は、斬新で忘れがたい倍音となって聴く者の耳に届いてくる。――

ピアノという楽器は普通「弾く」ものであり、音楽表現のために人が普段触れる部分は鍵盤、ペダルなど楽器の大きな器全体からみれば限られた部分である。しかし実際に音響が発生する弦やハンマーといった部分に手を加えて楽器自体の表現力を拡大しようとする発想が起こっても何ら不思議なことではない。鏡の様に照り返す漆黒の外板に囲まれた金色のフレームの中を、禁断のお仏壇の世界と思わなければの話だが。

事実、仏壇なぞ見たことも聞いたこともない人々の住む国では、ピアノの機構を操作するということ自体は決して目新しいことではなかった。ジョン・ケージはすでに60年前にはプリペア―ド・ピアノの作品を作曲している。更にケージの師ヘンリー・カウエルがピアノの弦を素手で弾く、たたくといった内部奏法を始めたのは1920年代のことであった。 プリペア―ド・ピアノ作品の誕生は、彼が関わっていたパフォーミング・アート上演用の伴奏音楽作曲に際して、打楽器の代わりにピアノを用いざるを得なかった事情にも由来している。すなわちケージはプリペアード・ピアノのつむぎ出す多様な響きを打楽器の音色の代替物としてまず認識し、その音色がより豊かに響くリズムを創造しようとしたのであった。

ケージは音楽に不確定性の要素を持ち込んだ。明確な理論あっての表現ならば音楽の世界は何でもあり、やった者勝ちという一見乱暴に見えるやり方で新たな境地を切り開いたことで、楽典でガンジガラメにされた世界から音楽を解放したその功績は非常に大きい。しかし、世界のアカデミックな現代音楽の流れは、皮肉にも獲得した自由から人間の感性の地平を広げる新たな世界を作り上げる結果にはならなかった。むしろ、音楽そのものの成立する制度的環境の検証に重点が置かれ、分析的な表現に走ることになり、音楽の作曲演奏される過程から作曲者や演奏者の意識や主観の排除という方向に向かうことになる。そしてプリペア―ド・ピアノも20世紀の実験音楽の大多数と共に埋没してしまい、音楽表現としての生命力を失ってもはや音楽史上の用語の一つとして思い出されるだけの、実体のない存在になり果てようとしている。

こうした状況の現代に、全く別の環境からピアノ全体を用いた表現による音楽活動を始めたのが宝示戸亮二である。宝示戸の奏でる旋律や音色は一般的な調性やリズムを取り払おうとする傾向がある点と同時に、非常に叙情的な側面を持っている。というのも彼の演奏が、演奏技術や音色上の純粋な実験といった方法論が先行した結果として誕生したものではなく、まず心の底から表現したい情念、展開したいモチーフというものが先に存在し、その結果たどり着いたものだからであろう。

例えば鍵盤のみの演奏ではじまるモチーフは、「やさしさ」や「なつかしさ」ともいうべき情感を伝えるものとなっている。特に曲2目『My Treasure』最初のモチーフに見られるペンタトニックな進行などは、現代の日本人にとっては非常に自然な表現であろう。こうした表現は、個人の具体的な記憶や日常の感情に基づいた秩序だったものではなく、人類が心の中に本能的に備え持つものとしての根源的な混沌(カオス)から来たものである。宝示戸の即興表現の本質は、個人ひいては人類が持つ普遍的な意識の底にある深層的なイメージの輪郭を演奏者が無意識に汲み取り、感性のフィルターにかけて再創造した音楽という点にこそ存在する。

また、5曲目で宝示戸が太く響かせる音色(サックスのマウスピースをつけた筒状の楽器? を用いている。)は、ザトウクジラの唄に触発されたものであり、低く沈鬱に広がるフレーズは、生息する環境を追われた鯨に限らず生きとし生けるものの心の底にある悲しみを表わすものに昇華されている。こうした表現は小手先の浅知恵で作り出せぬものであり、また全く考え無しのいきあたりばったりの発想からも決して生まれ得ないものである。 宝示戸亮二の演奏に接する時、演奏スタイルの奇抜さやパフォーマンス性の強さではなく、このような奏法でしか表現出来ない事柄や、この奏法によって生み出される情感とは何か?という点について注目するならば、奔放と感じられる演奏の中に宝石のようにきらめく繊細な一瞬をいくつも感じ取ることが出来るであろう。そしてそれらのきらめきの一つ一つとでもいうべきモチーフが豊かに大きく展開していく過程を必ずや発見することが出来るに違いない。

この演奏は1998年10月フィンランド、「タンペレ・ジャズ・ハプニング ’98」での演奏を録音したものであり、宝示戸の出演はプログラムの最終日であった。聴衆の好評を博したことはもとより、彼のアグレッシヴなパフォーマンスと深い音楽性は音楽祭のスタッフや参加した音楽家に多大な衝撃を与えるものであった。また、フィンランド国内で翌日の新聞に大きく紹介されるなど宝示戸の音楽は大きな波紋を呼び、後日ヘルシンキのフィンランド国立現代美術館KIASMA(キアズマ)で開催されたコンサートでは、タンペレでの演奏に魅せられた人々も急遽方々から駆けつけたという。

シベリウスやパルムグレンの作品に代表される、澄み切った音色の広がりある表現を大切にしてきたフィンランドの人々のことである。彼らにとって宝示戸のピアノがそこにあった時間は、日本人とはまた違った感覚で心の琴線に触れるものであったことであろう。